ENIGMA Chapter 2 – The Invention of the Engima Machine

Chapter 1 – Historical Background

Chapter 3 – The Substitution Cipher

Introduction

The breaking of the Enigma coding system was not a one-time event.

The Polish Cipher Bureau (which first decoded Enigma messages in late 1932/early 1933), Bletchley Park in England, and codebreakers in other countries had to deal with different versions of the Enigma machine, as well as ever-changing technical details and modes of operation. Methods devised by the Polish cryptanalysts in the 1930s no longer worked in the 1940s after the Germans made additional changes to the machine in 1938 and improved their flawed key exchange protocol in May 1940.

By this point Alan Turing had figured out a new way of cracking the code and had designed the Bombe, an electro-mechanical machine that could help break Enigma (and which later incorporated an important improvement made by Gordon Welchman). This, however, did not mean that cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park were able to continuously read Enigma messages throughout the war. Further changes to the machine caused setbacks and information blackouts. In addition, the German Navy used a more sophisticated and complex model that was much harder to crack.

In addition to the Enigma code, cryptanalyst also had to deal with the Lorenz cipher, a teleprinter code that was produced by a different machine, the Geheimschreiber, and was used between the German High Command and their army commands throughout occupied Europe. Breaking the Lorenz cipher in Bletchley Park lead to the creation of the Colossus, the world’s first digital electronic computer, an invention that was kept secret for decades.

It is also important to remember that while the main codebreakers deserve attention and praise for their breakthroughs, these would not have been possible without the tireless work of the countless other members of staff at Bletchley Park and at listing post throughout the country, many of whom were women, whose jobs included intercepting radio signals, deciphering, analysing and translating messages, maintaining the equipment etc.

Before I get to the fascinating story of Alan Turing, Bletchley Park and the equally intriguing Polish codebreaking efforts before the war, I’d first like to share some basic information about the invention of the Enigma machine. In Part 4 I will try to explain its basic functions with the help of a DIY paper cut-out version, as I think being able to visualize what happened inside the Enigma machine may make it easier to understand it and, by extension, the Bombe as well.

The invention of the Enigma machine

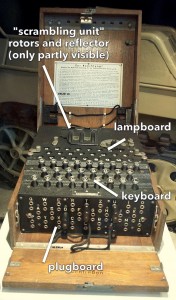

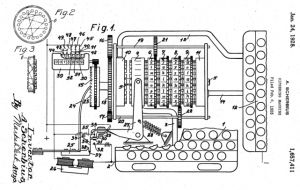

The Enigma machine, which would become one of the most fearsome systems of encryption in history, was invented by the German Arthur Scherbius in 1918. It was a battery-powered, electro-mechanical enciphering machine about the size and weight of an old-fashioned portable typewriter, and was kept in a wooden box. It consisted of the following three main parts, connected by wires:

- A keyboard with 26 keys for inputting each plaintext letter.

- A scrambling unit with three interchangeable wheels (also called rotors) and a reflector, which encrypted each plaintext letter into cipher. Each rotor had 26 inputs and 26 outputs which were wired to each other in a distinctive way. The scrambling unit was the most important part of the machine.

- A lampboard with 26 lamps that indicated the ciphertext letters during encoding, and vice versa during decoding.

A fourth important feature, the plugboard for swapping letter pairs, was later added to the military version of the machine.

When an operator pressed a key, an electrical pulse was sent through the wiring of the scrambling unit and illuminated the corresponding ciphertext letter. The exact electrical path was determined by the position of the three rotors, which changed with every keystroke as at least one of the wheels turned and advanced one position. This meant that pressing the same key repeatedly resulted in different ciphertext letters. If an operator typed the letter A once, it might illuminate the letter E, pressing the key A again might encode it as R, and so on. (I will go into more detail in Part 3).

Arthur Scherbius tried to market a commercial Enigma model to companies and a modified version to the military authorities of various nations. Neither effort was successful at first. Businesses such as banks said they couldn’t afford the machine and German military leaders were equally unenthusiastic. The latter were not yet aware of the role played by insecure ciphers in World War I (See further ENIGMA Part 1 – Historical Background). Thus very few Engima machines were sold at that time.

The military was shocked into action in 1923 when several British accounts of the Great War were published, among them Winston Churchill’s ‘The World Crisis’. These detailed the interception and decryption of crucial German coded messages sent during the war, which forced the Germans to admit that they had been playing ‘with open cards’. In the aftermath of these revelations, they initiated an effort to find ways of preventing a repeat of this cryptographic fiasco, which led to the decision that the Enigma machine offered the best solution.

Since the various moveable elements of the machine (the rotors and cables of the plugboard) could be set independently of each other, the resulting number of possible settings was astronomical. The early military version had roughly 10,000,000,000,000,000 different ways of being set up. If a hypothetical cryptanalyst could try one setting a minute, it would take longer than the age of the universe to check every possibility. This mind-boggling number lulled the Germans into a false sense of security: up until the end of the war, they never believed or even suspected that the code could be/had been broken.

By 1925 the military version of the Enigma machine was being mass produced in Germany, and it went into military use in 1926. The military model was different from the commercial one (different wiring in the scrambling unit, added plugboard), which by this time had also found a number of buyers interested in protecting commercial secrets, so even if companies owned a freely accessible commercial Enigma machine, they could not read traffic encoded on a military model. Over the next two decades, the military bought over 30,000 Enigma machines.

After Hitler came to power in 1933, the German army was reorganized and the Enigma machine played a critical role in this. The concept of Blitzkrieg (lightning war) involved fast, powerful attacks by infantry formations, backed by air support, and the capability of coordinating these elements at high speed and with absolute security. ‘Speed of attack through speed of communications’ was the catchphrase. At the beginning of World War II the Germans were overwhelmingly superior to the Allies in the field of radio communications.

Gordon Welchman, a codebreaker at Bletchley Park and co-creator of the Bombe, describes in ‘The Hut Six Story’, an account of his experiences during the war:

‘Because the Germans had done such a good job, the problems with which we were faced were unprecedented. Never before had radio signalling and cryptography been employed on such a large scale to provide battlefield communications.’ [p. 20]

Simon Singh writes in ‘The Code Book’ :

‘Scherbius’s invention provided the German military with the most secure system of cryptography in the world, and at the outbreak of the Second World War their communications were protected by an unparalleled level of encryption. At times, it seemed that the Enigma machine would play a vital role in ensuring Nazi victory, but instead it was ultimately part of Hitler’s downfall.’ [p. 142]

—

Previous post: Chapter 1 – Historical Background

Next chapters: 2 – The Invention of the Engima Machine, 3 – The Substitution Cipher, 4 – How Does the Machine Work? Part 1 and Part 2

FURTHER READING:

Books:

HINSLEY, F.H., & STRIPP, Alan. Code Breakers. The Inside Story of Bletchley Park. Oxford, 1993

KAHN, David. The Code-Breakers. The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. New York, 1996

KAHN, David. Seizing the Enigma. The Race to Break the German U-Boat Codes, 1939 – 1943. Revised Edition. London, 2012

McKAY, Sinclair. The Secret Life of Bletchley Park. The WWII Codebreaking Centre and the Men and Women Who Worked There. London, 2011

SINGH, Simon. The Code Book . The Secret History of Codes and Code-Breaking. London, 1999

WELCHMAN, Gordon. The Hut Six Story . Breaking the Enigma Codes. Oxford, 1997

Websites:

CRYPTOMUSEUM The Enigma Cipher Machine: Description of various different Enigma models, Retrieved April 2014

—

Enigma picture modified from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Enigma_Verkehrshaus_Luzern.jpg

Write a comment

You need to be logged in to leave a comment.